Each indigenous group has their own way of understanding, and relating to, the environment around them. The environments they live in are also different.Indigenous peoples have a wide range of lifestyles and ways of occupying a space, just as Brazil has a great diversity of natural environments. The Brazilian savannah (or cerrado) is very different to the Atlantic Forest and that is very different to the Amazon rainforest.Find out about these differences!

Do all Indians live in the same natural environment?

- No. They live in various natural environments. And each environment offers different natural resources for them to live off. Have a look at these examples:The pinhão is the seed of the araucária pine tree. This is a tree typical of the south of Brazil. The seed is used in many recipes of the Kaingang people.

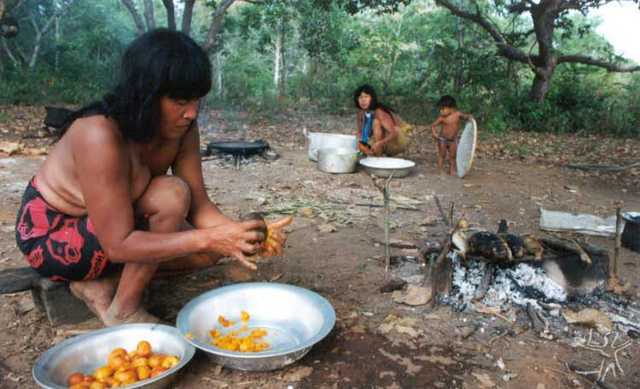

Cheiro de Pequi. Vídeo nas Aldeias, Imbé Gikegü, Takumã Kuikuro e Maricá Kuikuro Peoples living in the Xingu Indigenous Park do not know pinhão, because they live in the state of Mato Grosso, where there are no araucária pine trees. However, they have many recipes for pequi. This is a very common fruit in the Xingu region. It has been grown for many years, mainly in forest gardens which have been abandoned. Over the years these have grown into pequi orchards!

Is a natural environment dependent on the people who live in it?

It is in some ways. The relationship between any population and the place where they live affects the natural environment in many ways.

Beto Ricardo/ISA, 2005. Indigenous peoples have long known how to use natural resources without putting ecosystems at risk. They know that they are dependent on the environment and its resources in order to live. Because of this they have developed ways of managing the natural environments around them. This greatly helped conserve of the forests of what is now Brazil.Let’s look at how indigenous peoples live in a few different ecosystems. You can find out here, how they relate to the environment around them and, at the same time, change it.

The Ikpeng and the spirits of their natural environment

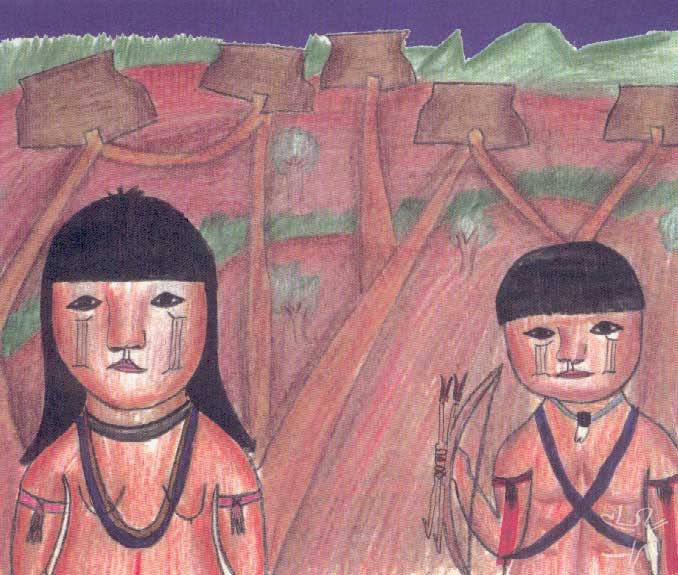

Opote e Maiua Ikpeng, 2001. The Ikpeng speak a language from the Karib linguistic branch. They live in the Xingu Indigenous Park, in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso.The text below is taken from the book Ecologia, Economia e Cultura. It describes the relationship between the Ikpeng, the natural environments around them, and the spirits that they believe exist in each of these different environments.

The spirits of different ecosystems

In the science of the Ikpeng people, all beings have life. A rock might not seem to be alive, but actually it is. If it was not alive it would not exist, and it would not attract the fish that swim around it. In our society, there is a rule for a person who has a small child. Such a person must not climb onto a rock. This is because a rock is a house of the spirits for fish and other beings. The rock may be very dangerous. Its spirit may steal the child and keep it.

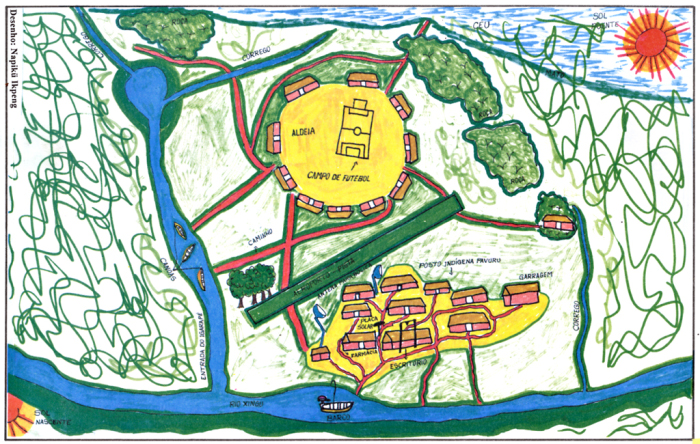

Geografia Indígena, 1996. ISA/MEC/PNUD. A beach is also a living being. It has a very strong spirit. That is why a beach does not disappear or swim about. A beach is tricky. It attracts various spirits.Nature is made up of different ecosystems because different regions are home to different life-forms and spirits. That is why each different ecosystem has earth with a different colour and is covered by a different type of forest. It is the same with human beings. Some are fat, tall, thin, short. Each has their own life and their own spirit.We Ikpeng have ways of classifying the spirits of the different ecosystems:

- Areas of forest where trees are tall have a guardian called Enoy. She is a woman, but she does not have any genitals. She is a hunter armed with an arrow. She looks after this kind of forest.

- Areas of forest where trees are medium-sized have their spirits too. They are called Mïyegu and Wiwoningkïn (a kind of giant armadillo that lives in the earth). The Wiwoningkïn are the same as humans because they cannot go hunting alone. It is dangerous. They have to take care.

- Kanarot is a spirit of areas of forest where the trees are short. He is found where there are tucumã palm trees. He is the same as us, but covered in various types of leaves.

- Otomowïra is a spirit of both areas of forest where the trees are tall, and areas of forest where the trees are short. He looks like a skeleton of a dinosaur, and he is the reason why you must not whistle when you go hunting

- Apariko is a spirit of areas of forest where the trees are short. He looks like a whiptail lizard.

(Text provided by Korotowi, Maiua e Yokore Ikpeng)

The Kisêdjê people and how they cultivate plants

The Kisêdjê are also known as the Suiá. They live in the Xingu Indigenous Park, where they are the only people to speak one of the Jê languages.This text is taken from the book Ecologia, Economia e Cultura. Have a look to find out how the Kisêdjê grow crops in their gardens. It also explains why they have to pay attention to changes in the natural world around them if they are going to get good harvests.

The garden

Ecologia, Economia e Cultura (1), 2005. Atix/ISA. We notice signals from nature which tell us when it is time to make clearings and when to plant crops. One of the natural signals my people look out for is when it is time to collect murici (the fruit of golden spoon trees). Another sign is when the leaves of the trees turn yellow. This means that it is time to start work. These are signals to start growing crops and cutting trees to make our gardens.There is a tree with a yellow flower, called the golden trumpet tree. When this tree has flowers it is another sign that it is time to start growing crops and cutting trees to make our gardens. There are also signals in the stars. The ones that are close together, across the sky towards the sunset, head back towards the sunrise. This means it is already time to start cutting trees to make a clearing.We know the right time to burn our clearings from the song of the bush cricket. It is a very hot time. A dry time. The time to burn is when the bush cricket sings harshly, and there is a bright purple flower on the trees with the leaves we use for scraping. Another signal is the song of the little nightjar bird. It is asking for rain to come soon.We have a ritual for the plants in our gardens to sprout and grow well. It is a very sad ceremony for us because, in the past, an old woman got burnt and, after this, maize was created. It was introduced to the Kisêdjê by a rat.

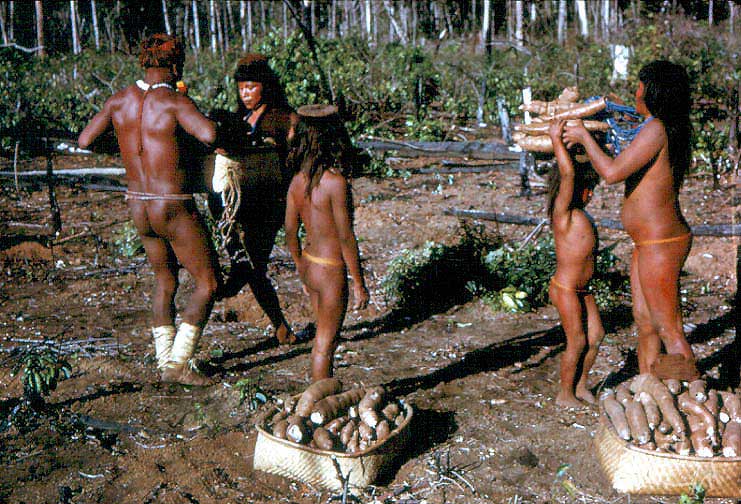

Harold Schultz, década de 1960. The time to plant is when the first rain falls to the earth. That is when plants grow well. We plant manioc roots separately so that they do not get in the way of other crops. Potatoes, bananas, and other crops have to be planted together.We must not let ants near to what we grow. If we do, they will eat the plants’ leaves. We use manioc poison to get rid of ants. This is how we look after our plants. We do not use fertilizers. We kill large and small ants with manioc poison.We harvest maize when the rain stops a bit. There are other signals for when to harvest other crops.(text Kaomi Suyá Kaiabi and Petoroty Suyá)

Living in the Brazilian savannah (or cerrado)

Rosa Gauditano The Xavante live in the central zone of the Brazilian savannah (or cerrado). This is a region of bush vegetation with strips of forest along the riverbanks, which are known as mata de galeria.

This savannah region has two distinct seasons: a dry time called winter, and a rainy season known as summer.

Brazilian savannah (or cerrado)

Brazil contains huge areas of savannah. This environment covers about one and a half million square kilometres of the centre of the country. There are many different types of vegetation in the savannah. Some parts of it are open plains. Some parts are covered by grasses, bushes and small, twisted trees. In other parts there are thicker areas of forest (known as cerradões). Summer rains turn this into a green landscape. During the winter the grass dries out, the trees lose their leaves and the fallen leaves and twigs create conditions for forest fires.

Júlia Trujillo. Many trees in the Brazilian savannah flower during the dry months of May to September. Even though there seems to be no water about at this time of year, trees such as the golden trumpet tree are able to absorb moisture from the water table deep underground.

Not all the species in this savannah region have been identified. But it is known that the Brazilian savannah is extremely rich in flora. (This means all the plants in one particular area.) It is home to more than 6 thousand different species. The commonest ones are plants from the bean and peanut families. There is still much to be discovered about the wildlife of the region. We know a bit about species found there, but little about how they actually live. Some insects, such as termites, ants and bees are very important, both for the quantities and diversities they are found in, and because of the relationships they have with other life forms. Bees, for example, play a fundamental role in the creation of fruits and seeds. Other common animals in this region are boa constrictors, vultures, emus, toucans, hawks, giant anteaters, wolves, armadillos and deer.

What do the Xavante people eat?

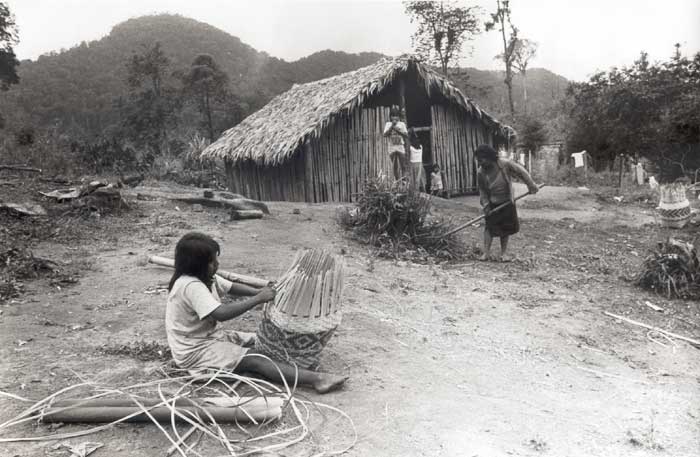

Júlio César Borges The Xavante’s traditional diet is based on gathered food. This is mainly collected by the women. It includes wild root, nuts, fruit and typical vegetables of the region where they live. Men provide meat from hunts and some fish to add to the gathered food.

Until 1960, the Xavante would get this food on hunting and gathering expeditions. They would go on long journeys, some lasting several months. On their journeys, family groups would seek out the natural resources of their region. If Xavante people were still off on their journeys across the Brazilian savannah during the dry season, they would go back to their villages to spend time together and hold festivals. Then they would return to their hunting and gathering expeditions.

Have things changed these days?

The days of these migrations across the Brazilian savannah are just about over. The amount of land available to indigenous peoples has been greatly reduced and, with it, the numbers of animals that can be hunted. The Xavante still go on hunting and fishing journeys. But they are shorter. They last for one or two nights.

Do the Xavante miss eating hunted meat?

Yes. The Xavante’s main sources of protein used to be hunted meat, and the fish that they caught. These sources barely exist any more. The Xavante have little land. They are unable to hunt any more. Without protein, our bodies become weak and vulnerable to illness.

Meat was also an important element of their festivals and weddings. You need a lot of meat to feed a whole community. So their inability to hunt these days, affects not only the Xavante’s nutrition but their ability to hold traditional rituals.

Why were the territories of the Xavante reduced?

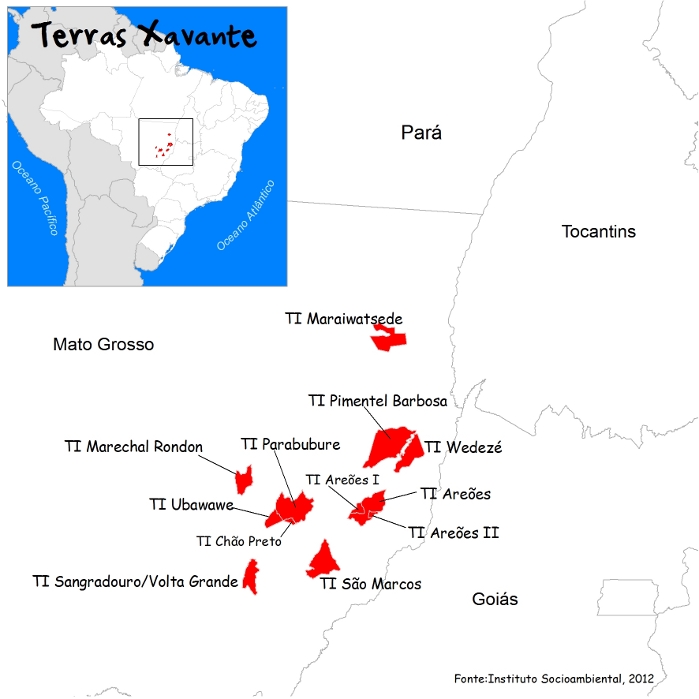

Instituto Socioambiental, 2012. A part of the Brazilian savannah has been taken over by farmers for rearing cattle and for soya bean and rice cultivation. As well turning large parts of what was Xavante territory into farmland, these types of agriculture involve deforestation and burning. So they threaten the local environment.

André Villas Bôas/ISA, 2002. The fertility of the soil is reduced, rivers are polluted and animals abandon the region. Agriculture which clears away large stretches of forest to grow one single crop is known as monoculture.

Living in the Atlantic Forest

The Guarani M’bya have long lived in the Atlantic Forest which runs down the south and south-east coasts of Brazil. The ecosystem of the Atlantic Forest is very important for the Guarani M’bya. The preservation and development of their culture is dependent on sustaining the biodiversity of this forest.

Fundação SOS Mata Atlântica and map of biomes from Brasil. Primeira Aproximação. IBGE, 2004. The Atlantic Forest

The Atlantic Forest is one of the most threatened environments on the planet. For centuries now, people living in the forest have been exploiting it in predatory and destructive ways.

The Atlantic Forest stretches across 17 different Brazilian states, from Rio Grande do Norte in the north, to Rio Grande do Sul in the south. It is an area which contains Brazil’s biggest cities. And it is where the majority Brazilians live.

Even so, the forest sustains a very large biodiversity. Until the sixteenth century, the Atlantic Forest covered about 15% of what is now Brazil. Today, after so many years of exploitation, only 7% of the original forest remains.

It is important to remember that the Atlantic Forest is made up of various ecosystems, including mangrove swamps, restingas (areas of beach vegetation) and semi-tropical forest.

Silvia Futada, 2009. Among the well known plant species are: the paraná pine tree, the juçara palm tree, the jequitibá tree, the brazilwood tree, the mate-tea plant and great numbers of bromelias and orchids. It is estimated that the forest contains 20 thousand different plant species!

It is also home to animals including pumas, jaguars, wildcats, tapirs, deer and peccaries.

Is it true that the Guarani M’bya people are very knowledgeable about the environment they live in?

Yes. They have given names for all kinds of vegetation and natural features of the landscape. Here are some examples:

- Yvy yvate is the name for hills and mountain ranges;

- Ka'agüy poru ey are areas of virgin forest – places people have never touched, and should never touch because they are sacred;

- Ka’agüy karape’i are areas of bushy forest and short trees, which are good for making gardens and building houses;

- Kapi’i are areas of vegetation containing species good for making roofs for houses such as satintail grass (known locally as sapé).

Giving names to things classifies them and it is also a way of relating to them.The way the Guarani have named all the elements in their environment shows how closely they relate to the environment where they live.

What sort of a relationship exists between the Guarani and the environment where they live?

It is a relationship based on knowledge and exchange. The Guarani know where, in their territory to find the natural resources necessary for their survival.

Milton Guran, 1988. The wide range of plant products that they gather is an example of how this relationship works. They know which plants cure illnesses, which can be eaten, which are good for building houses and which are good for making handcrafts. The roofs of their houses are traditionally made from pindo, which is a palm tree typical of their region. To conserve supplies of meat, they do not hunt animals which are tending to young. And they actively plant important species such as maize, peanuts, manioc, sweet-potatoes and tobacco.

The Guarani choose where to build their villages with great care. The environment around a village needs to contain the natural resources they need to maintain their lifestyle. As well as environmental factors, religious and social questions influence their choice. They look for places that will allow them to live according to their traditional rules and customs.

Why do the Guarani exchange seeds?

Maria Inês Ladeira. Exchanging sees is an important custom for this indigenous group. It prevents plants that are vital sources of food from becoming extinct. The Guarani visit relatives in other villages to swap peanut and maize seeds and seedlings.This custom is also a ways of encouraging the inhabitants of different villages to interrelate. It leads to weddings and other festive gatherings.

Is the Guarani’s traditional environment in good condition?

Unfortunately not. The Guarani do not hunt when animals are reproducing. This conserves certain animal species vital for their survival. Nevertheless these animals are evermore scarce. This is because of the intensive occupation and deforestation of the regions around their villages. Conservation of the Atlantic Forest is of utmost importance to the Guarani. If the forest environment is damaged, it has serious consequences for the lifestyle of these people.

Make sure you read the text below!

‘Everything was free for us, but now everything is forbidden. We can no longer cultivate crops in clearings as we did in the old days. The least we deserve is this little bit of land we are asking to be mapped-out and given to us. If they take this small piece of land from us, we will have nothing left. (...) We want the guarantee of some land, so that we are free to live according to our culture, and cultivate our culture by teaching it to our children and our grandchildren. Because these days, when we do not have a true territory any more, we cannot fully live our lives and our culture (nhande reko)’. (A section from a letter from the Morro dos Cavalos community, in the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina, sent to government authorities in 2002).Living in the Amazon

More than 800 Indians live along the banks of the River Uaupés and its tributaries. They make up about 200 social groups, and come from 17 different indigenous peoples. They speak languages from three different linguistic branches: Tukano, Arawak and Maku.

The Amazon

The Amazon region takes up almost 50% of Brazil. Most of the forest covering this region is on low land. It consists of tropical rainforest (which never dries up during the year) and seasonal rainforest (which is dry for some months of the year). The Amazon’s location, on the equator, means that it receives plenty of light and heat from the sun, and is also covered by a mass of humid air. This guarantees a damp, hot climate, with high temperatures and intense spells of rainfall.

The Amazon is home to the largest system of rivers and water courses anywhere in the world. At any one time, it holds about a fifth of all the fresh water on our planet.

Você deve dar crédito ao autor original, da forma especificada pelo autor ou licenciante). It is the region with the greatest biodiversity on Earth. It sustains medium-sized and tall trees. Some of them grow 50 metres tall. There are large quantities of vines, bromelias and orchids. And the Amazon is home to one of the largest aquatic plants in the world: the vitória regia.Other common species in the Amazon forest are guaraná, jenipapo and urucum. Jenipapo can be used to make black paint. Urucum is used to make red paint. Both of these plants are used by indigenous peoples for body painting. The Amazon is also known for its great diversity of fish. Among these is the pirarucu, one of the biggest fresh-water fish in the world. It can grow three metres long and weigh 200 kilos. There are many other kinds of animals found in the Amazon. These include three-toed sloths, armadillos, jaguars, anteaters, parrots, howler monkeys, pygmy marmosets and many other types of monkeys.

Why are rivers important to the Tukano, the Arawak and the Maku?

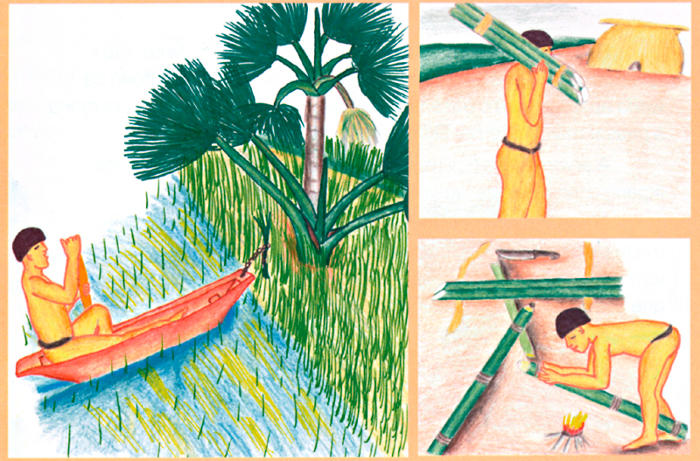

Aloisio Cabalzar, 2002. The peoples who speak Tukano e Arawak languages mostly live along the banks of large and small rivers. They are highly skilled at fishing and cultivating plants. They mainly travel from place to place by canoe.

The river is the main way Tukano peoples measuring distances. It is how they get from place to place and communicate with other communities. The Maku people, on the other hand, live further into the forest alongside the small rivers known as igarapés. They tend get from place to place by walking. Because of this, they are more knowledgeable than other peoples about the forest, its paths, its natural resources, its wild fruits and insects. They are excellent hunters.

What is the relationship between the Tukano and the Maku?

For many years the peoples who speak Tukano languages and the Maku have had trading relations. The Tukano offer the Maku their crops: manioc flour, beiju, tapioca e other foodstuffs made from manioc roots. The Maku offer the Tukano (who are known as ‘Indians of the river’) smoked hunted meat and fruits gathered in the forest. The Maku also sometimes work for the Tukano in exchange for items such as matches, tobacco, clothes and hammocks.

When do they trade these items?

These things are traded according to the life-cycles of the plants, fish and animals, and the way they become available at different times of year.

For the indigenous communities of the River Uaupés it is very important that these cycles of reproduction are respected. They believe the rituals they carry out contribute to the balance of the natural world. They believe their rituals help plants and animals to reproduce. They help the seasons come as they should. And they help the natural world continue making fruits and resources available to humans.

How do these peoples grow plants?

The peoples of the River Uaupés grow plants very differently to modern agriculture. Many contemporary farms produce just one type of crop. This results in poor soils, and leads to excesses of some crops and shortages of others. In indigenous gardens, many types of crops are grown side by side: different species of maize, of manioc, of potatoes, of peanuts, bananas etc.

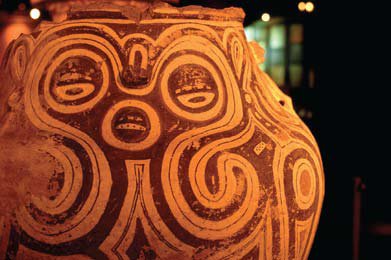

The diversity of species grown in a particular region has great value for these peoples. Diversity features in their myths. (In the old stories they tell about how their peoples learnt to cultivate plants.)

What other places are important to these peoples?

Areas of low forest known as caatinga are useful sources of dried leaves used for roofing houses. These include moretillo palm trees (known locally as caranã) and sororoca grass.

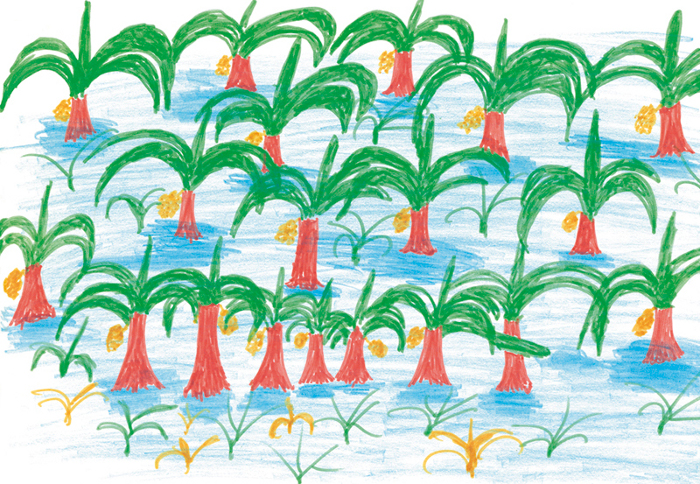

Rachel Lange Areas of bushy vegetation are good for catching small animals such as agoutis. They are also rich in medicinal plants. These areas are also important because they are home to pupunha palm trees, buriti palm trees and cashew trees, all of which give fruit for many years.

The igapós are also important. These are areas flooded by rivers for certain periods of the year. They are where fish reproduce. For this reason they are looked after very carefully by indigenous peoples. Igapós are also areas rich in vines and rubber trees.

The knowledge and techniques of indigenous populations in this region have developed over many hundreds of years of finding out about the world around them. This accumulated knowledge is fundamental in creating ways of treating environments which do not degrade or impoverish them. This is why indigenous peoples manage to sustain ecological equilibrium around them.

Living in cities

Instituto Socioambiental, 2009. The Pankararu are a people originally from the state of Pernambuco, in the north east of Brazil. However, from about 1940, a number of them started coming to work in the large Brazilian city, São Paulo. They came to earn money to send back to their families. At first, it was only men who came. They worked for a time in the city. Then they returned to their villages. But, as time passed, this changed. Women started migrating too, and Pankararu families began springing up in the city. Since these people did not have enough money to live in more expensive neighbourhoods, they settled on the outskirts. And they ended up in one particular shanty town called Real Parque.

Was it important for them to live together in one area?

Yes. Various Pankararu people started families in São Paulo and lived nearby each other. This way they could keep strong bonds and help each other out. So, although they were living in an environment quite different to where they were from, they were able to hold onto their identities. The Toré ritual for example is held every week in the Real Parque shanty town, led by a Pankararu shaman.

Sources of information

- Aloísio Cabalzar

Peixe e gente no Alto Rio Tiquié: conhecimentos tukano e tuyuka, ictiologia, etnologia (2005).

- Beto Ricardo e Maura Campanili

Almanaque Brasil Socioambiental: Uma nova perspectiva para entender a situação do Brasil e a nossa contribuição para a crise planetária (2008).

- Dominique Gallois

Terras ocupadas? Territórios? Territorialidades?, no livro Terras indígenas e unidades de conservação da natureza: o desafio das sobreposições (2004).

- Beto Ricardo

“Os índios” e o futuro da sociodiversidade nativa contemporânea no Brasil, no livro A temática indígena na escola: novos subsídios para professores de 1° e 2° graus (1995).

- Maria Inês Ladeira e Priscila Matta

Terras Guarani no Litoral (2004).

- Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (ATIX) e Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)

Ecologia, Economia e Cultura - livro 1 (2005).

- Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (ATIX) e Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)

Ecologia, Economia e Cultura - livro 1 (2005).

- Proyecto Cultivando Diversidad

Experiencia de manejo de recursos genéticos amazônicos por indígenas del Xingú, no livro Cultivando Diversidade en América Latina (2005).

- Laura Graham

Verbete Xavante from virtual Enciclopedya Indigenous Peoples in Brazil (2008).

- Maria Inês Ladeira

Verbete Guarani M'bya from virtual Enciclopedya Indigenous Peoples in Brazil (2003).

- Equipe do Programa Rio Negro do Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)

Verbete Etnias do Rio Uaupés from virtual Enciclopedya Indigenous Peoples in Brazil (2002).

- José Maurício Arrutti

Verbete Pankararu from virtual Enciclopedya Indigenous Peoples in Brazil (2005). [portuguese]

- Website Indigenous People in Brazil

Portugues

Portugues

German

German

Spanish

Spanish

Norwegian Bokmål

Norwegian Bokmål

Where they are

Where they are Ilya e o fogo

Ilya e o fogo String figures: Ketinho Mitselü

String figures: Ketinho Mitselü Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene

Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene