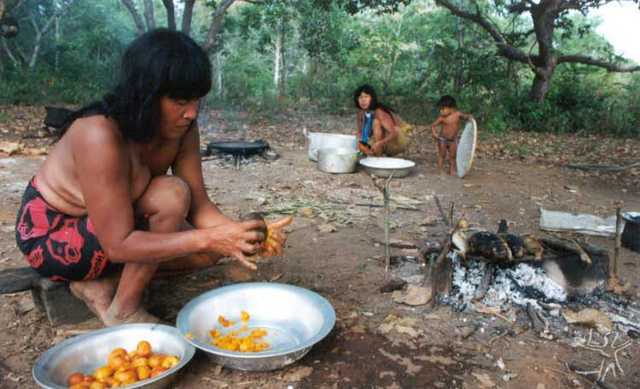

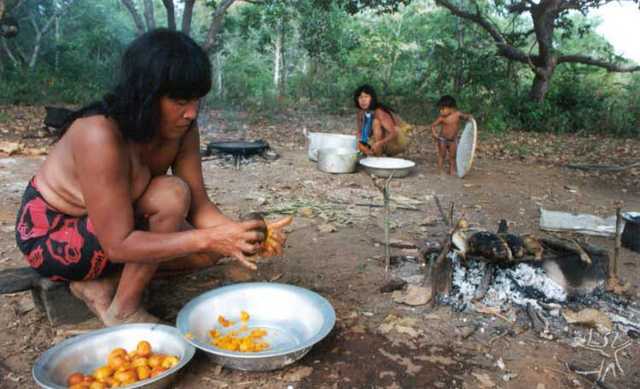

Indigenous peoples spend a lot of time making sure they have enough to eat. This is because, on the whole, they have to find or produce their own food.

They may look after animals such as chickens and pigs, go on hunting and fishing expeditions, gather wild fruit in the forest, tend to the crops growing in their gardens, or harvest what has been grown.

All these activities require detailed knowledge of the region where they live. They need to know about seasonal variations in rainfall, about how specific animals behave, about the seasons when different fruits ripen, and about the best times of year for planting and harvesting crops.As well as producing food, they have to make the tools and objects that they use. Among other things, these include traps, canoes, baskets, bows and arrows, and blow-pipes.

What sorts of work do indigenous peoples do in their gardens?

- In indigenous societies, both men and women help to grow crops. But they play different roles.

The men are responsible for clearing land for cultivation. First they cut down an area of forest. Then, when the felled vegetation has dried, they burn it. This clears the area and the ashes make good fertilizer. Then the men tidy the clearing, getting rid of unburned branches and other remains of trees.

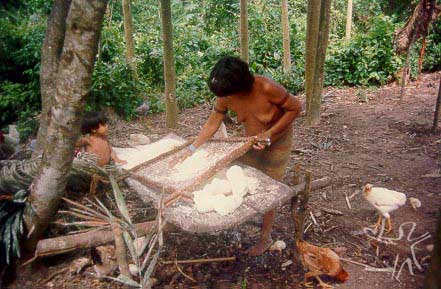

Mulher Guajá do Posto Indígena Guajá, TI Alto Turiaçu, ralando mandioca. Foto: Louis Carlos Forline, 1998. Women do the rest of the work. When the first rains fall, they plant species such as maize, beans, manioc, peanuts and yams. They keep the area tidy and pull up weeds which might stop their plants from growing. When their crops are ready, the women harvest them and carry them back to the village in baskets made from dried leaves.

Find out how the Tuyuka grow crops. They live to the north of the Amazon region, near the River Negro and the River Uaupés.

Tuyuka domestic utensils

Índia hupda do Médio Tiquié. Foto: Aloisio Cabalzar/ISA, 2002. The crops harvested in our gardens are transported back to our villages using aturás. These are baskets made from vines. People carry them on their backs, using a strap around their heads.

The Tuyuka do not make these carrying baskets themselves. Another indigenous group called the Hupda make them. The Tuyuka trade them for things that the Hupda need. This might be salt, aluminium pans, clothes, manioc flour or manioc roots.

The upper reaches of the River Negro are home to at least 20 different indigenous peoples. The Tuyuka are one of them. Several different peoples are our neighbours: the Tukano or Yebamasã people, the Bará people, the Barasana, the Hupda, the Desana... Others live along rivers further away, such as the Baniwa.

Canoa tuyuka. Ilustração: comunidades Tuyuka de Pari Acima, Alto Rio Tiquié. Fonte: Histórias tuyuka de rir e de chorar. Associação Escola Indígena Utapinopona Tuyuka, FOIRN e Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), 2004. The Hupda are best at basket weaving. The Tuyuka are experts at making canoes. The Desana make baskets out of dried arumã grass. These are used for serving bread made out of manioc which is called beiju. The Baniwa, meanwhile, are the one people who make manioc graters.

There is a big exchange network in the area. This ensures that Baniwa manioc graters reach all the other ethnic groups. And the same is true for Hupda aturás, Tuyuka canoes and so on.

(Text provided by the Tuyuka of Pari Acima, on the Upper Rio Tiquié)

Hunting

O Araweté Mo´inowï-do fazendo flechas. Foto: Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, 1982. Men do hunting. Sometimes they go alone. Sometimes they go in groups. Hunting can happen near a village, or it can happen much further away. During the longer hunting trips, men spend several days camped in the forest.

Traps, bows, arrows and other things are important to ensure a hunt is successful. Men make these on a day-to-day basis.

O Araweté Iriwopay-ro num acampamento de caça. Foto: Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, 1981. Hunters need to have a very good knowledge of animal behaviour if they are going to bring home plenty of meat. They need to know which animals come out at night, and which come out during the day; what different animals like to eat; if animals live alone or in a herd; what tracks or smells they leave behind; and where they usually hide. With this information, it becomes much easier to find animals, prepare a hunt and make traps. Dogs are also sometimes used to help find the animals in the forest.

Fishing

Peixes assando. Terra Indígena Enawenê-Nawê, Mato Grosso. Foto: Vincent Carelli, 2009. Fish is a very important foodstuff for many indigenous populations. They know, and use, various fishing techniques. The commonest techniques are: putting timbó (a type of vine) or another poison into the water; fishing with hooks and lines; using traps; firing arrows... In some communities only the men fish, and they often spend several days camped near rivers and lakes. Elsewhere, fishing is also done by women, or carried out by whole families. When a whole family fishes together the work is a lot of fun!

Find out about the importance of fish to the Enawenê-Nawê people:

Do you know what ‘hitting with timbó’ means?

Hitting with timbó is a common type of fishing among indigenous peoples. É uma atividade que geralmente precisa de muita gente, tanto para o seu preparo, quanto para a coleta dos peixes.

Timbó usado pelos Ikpeng em suas pescarias. Foto: Rosana Gasparini/ISA, 2006. Large numbers of people usually take part in making the preparations and catching the fish. Timbó is a vine that grows in the forest. It is cut into pieces. These are soaked in water. Then the mixture is beaten with wooden pounders until the pieces are reduced to splinters. Once a pulp has been made, it is shaken about under water where fish live. A blue-white substance is released. It looks a bit like soap powder. This substance is timbó. It is poisonous to fish. Although the fish do not die straight away, they become slow-moving and are easily hit by arrows or caught. This way, many fish are piled up and carried back to the village, where the people prepare a big feast!

Find out about the importance of fish to the Enawenê-Nawê people:

Fishing among the Enawenê-Nawê

Enawenê-Nawê pescando. Terra Indígena Enawenê Nawê, Mato Grosso. Foto: Vincent Carelli, 2009 The Enawenê-Nawê, who live in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, do not hunt for meat and rarely eat birds. They live on food grown in their gardens, such as manioc and maize. And they eat fish. For them, fish are very important. They are a fundamental part of their festivals, and are also used for trade.

Barragem construída para auxiliar os Enawenê Nawê na pesca, Terra Indígena Enawenê Nawê, Mato Grosso. Foto: Vincent Carelli, 2009. These people have an excellent knowledge of the reproduction and migration patterns of fish. The men plan collective fish-catches based on this knowledge. These fish-catches normally take place in February and March. This is also when they carry out the Yãkwá ritual.

To catch all the fish necessary to carry out this ritual, they build dams in the river, which stop fish swimming past. They also use traps. With these techniques they manage to catch a lot of fish. The fish are taken to the village and they feed the entire community for several months. The Enawenê-Nawê smoke fish so that they do not go bad. This guarantees that they provide many meals. As well as the big fish-catch for the Yãkwa ritual, the Enawenê-Nawê go fishing as families. On these expeditions they fish with timbó, with hooks and with small traps left in streams.

Making food!

Find out a bit about what different indigenous peoples eat, and how they prepare their food.

The Xingu Indigenous Park is in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso. It is home to many different indigenous peoples. These peoples speak several languages and have different social and cultural traditions.

There are also many different types of food cooked in the region. Do you have any idea what they eat in these communities and how it is cooked?

Have a look at some recipes from different indigenous groups in the Xingu Indigenous Park!

Kanape or manioc bread with peanuts

Desenho de Moreajup Kaiabi. Fonte: Aprendendo Português nas escolas do Xingu (livro 2). Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (ATIX), 2005. First of all, a woman fetches manioc roots from a garden. Back in the village, the manioc is soaked in water. Once it has softened, it is taken out of the water and peeled. Then the manioc is left to dry in the sun. When dry, the manioc is mashed in a large pestle and mortar. After mashing and sieving the manioc, another pulp is made by crushing peanuts. Then you mix the manioc pulp together with the peanut pulp, moisten it a bit and kneed it into a ball.

A fire has to be made. When the fire dies down, the bread is cooked on the embers. Once it has been slightly toasted it is ready to eat.

(Recipe provided by Moreajup Kaiabi)

Mutap

Desenho de Awatat Kaiabi. Fonte: Aprendendo Português nas escolas do Xingu (livro 2). Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (ATIX), 2005. First a man goes fishing. He brings back fish for a woman to cook. The fish are gutted and scraped. Then the fish are put in a pan and cooked with water, salt and chilli peppers. A fire is lit and you wait for about forty minutes for the fish to cook. Once the fish has softened, the woman puts mutap flour in, and mixes with a wooden bowl or stirrer. When it is ready, you eat it with maize porridge, peanuts and rice. We Kaiabi people sometimes put other ingredients in mutap such as taioba leaves, and different types of manioc leaves. With these ingredients mutap tastes really good.

(Recipe provided by Awatat Kaiabi)

What is eaten during reclusion?

- When a boy or a girl approaches adolescence, it is time for them to learn about things they will need to do when they grow up and have families of their own. In many indigenous societies, girls and boys, at this age, are taken away from the community for a time. They only remain in contact with their closest relatives, who teach them what they need to learn. This is known as reclusion. During this period of reclusion young people have to obey the rules of the particular indigenous group that they are a part of.

The text below is taken from a book called Saúde, Nutrição e Cultura no Xingu (2004). It describes this phase among the Yudjá people, who live in the Xingu Indigenous Park.

A Yudjá girl in reclusion

At the start of the reclusion, the girl must not eat certain things such fruits which ripen quickly. This means bananas, papayas, watermelons and forest fruits such as api and ingá. The girl must not touch a fire or cook any food. It is a time when only the girl’s mother and her elder sisters can look after her. She is not allowed to have contact with anyone except her family.

Desenho de Yapariwa Yudjá. Fonte: Saúde, Nutrição e Cultura no Xingu. Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (ATIX)e Imprensa Oficial, 2004. Girls go into this reclusion straight after they have their first menstruation. Boys also go into reclusion. During this time they are only allowed to eat unsalted fish, manioc porridge, manioc bread and fine manioc flour.

There is a meaning to this practice. When a girl goes into reclusion, her mother, sisters or her grandmother teach her how to make hammocks, weave in different styles, do body painting and decorate handcrafts. For a young man it is the same thing. His father can teach him how to make a bow and arrow, a sieve, a club, an oar and other things that he will need to know how to do.

While a girl is in reclusion, her mother and father give her special herbs. Some herbs will make her vomit to clean out her body. Another is put into the water she washes in. The boys are given many herbs. Some make him vomit. Some are put into the water he washes in. Some are dripped into his eyes or rubbed on his body.

It is a time when a young person’s life changes. They leave behind their childhood and become adults.

(Text provided by Yapariwa Yudja)

The Wajãpi people live in the Brazilian states of Amapá and Pará, and also in French Guyana. During their time in “reclusion”, Wajãpi girls have to eat very different food to normal. Here you can find out what they can and cannot eat during this time. The following text was taken from a book by researchers and bilingual Wajãpi teachers: Jane Reko Mokasia – Fortalecendo a Organização Social Wajãpi (2008).

The reclusion of a Wajãpi girl

We have a tradition of putting a girl into reclusion when she has her first and her second period. The rules are: do not eat just any food, do not talk to people, do not go out into sunlight, do not get wet with the rain, do not walk on earth, do not think about anything, do not sleep much, do not wash in the river.

All these rules are respected. The girl must not break them. If a girl does break them, it can cause many problems. She may die. She may suffer long-lasting illness. Or other things may happen. Because of this, her grandfather, grandmother and her mother will talk to her, warn her, and advise her about these dangerous things.

When the girl has her first period she goes into reclusion. Because of this, she cannot eat some types of food. For example she must not eat bush-pig or peccary meat, potatoes, yams etc. If the girl eats the wrong kind of meat, marks will appear on her body. These might be, for example, little lumps. When a girl is in reclusion it is her father and her mother who will choose the right food for her. She can eat manioc bread, meat of the nambu bird and some fish such as traíra. If the girl eats just any food then she will have nightmares and grow old quickly.(Text by researchers and bilingual Wajãpi teachers)

What do the Tuyuka eat?

The text below was taken from the book Histórias Tuyuka de rir e de assustar (2004). It describes the main types of food eaten by this group, who live in the upper River Negro region, to the north east of the Amazon rainforest.

Fishing and hunting among the Tuyuka

Sometimes the Tuyuka go to fish and hunt far from where they live. They go to rivers where there are lots of fish. They make a shelter out of dried leaves called tapiri. They make a fire to keep warm at night, to cook on and to smoke (or moquear) the fish that they catch.

They spend days and nights fishing, and they hunt animals when they can.

The Tuyuka men do a lot of fishing. Fish are their main source of protein. They eat more fish than meat.

Tinguijada tuyuka (peixes na canoa, depois de pescaria com timbó). Pupunha, alto rio Tiquié, Colômbia. Foto: Aloisio Cabalzar/ISA. The Tuyuka have many sorts of fishing equipment. These include timbó, rods for lifting fish out of the water, pens to keep live fish in, and different types of fish traps called matapi, jequi and caiá. They also use industrially-made equipment such as metal hooks and nylon fishing lines. The best place to hunt animals is deep in the forest, far from signs of human life. These areas are good for hunting but they are also dangerous.

Hunters often take rifles with them. Some have hunting dogs which can track down animals.

In the past, Tuyuka men mainly hunted with bows and arrows and blow pipes called zarabatana. A zarabatana is a long tube made from a palm tree with the same name. These trees are hollow. Small poison darts are fired out of the tubes by blowing down them. If they hit an animal, the poison paralyses it. Blow darts are mainly used to shoot monkeys and birds from high in the trees.

Among the animals caught on Tuyuka hunting trips are tapirs, bush pigs, monkeys and armadillos. The men also catch reptiles to eat, including lizards, tegus and alligators.

A few animals, such as tortoises and grey-winged swans, are captured but not eaten. They are kept and looked after as pets.

(Text provided by the Tuyuka communities of Pari Acima, on the Upper River Tiquié)

Gardens

he Tuyuka make large gardens in clearings in the forest. They plant manioc every year. There are many different varieties of manioc, including macaxiera, aipim and mandioca brava. Mandioca brava contains a poison which has to be extracted before the manioc can be eaten. So it is treated first. It is grated and squeezed, to separate the pulp (known as the massa) from the poisonous liquid (known as the manicuera or tucupi, depending where you are in the Amazon). The liquid is boiled until all the poison evaporates. Then it can be eaten. The pulp is turned into a kind of bread. It is toasted over wood burners and turned into large circular pieces known as beijus.

Roça da Dona Amélia (Tuyuka) Comunidade São Pedro, Alto Rio Tiquié, Terra Indígena Alto Rio Negro, Amazonas, Brasil. 05/2005 Crédito: Beto Ricardo/ISA Each family has between 3 and 5 gardens to look after. They will always be at different stages. While one is being planted, another is already growing, and another is ready for harvesting. The clearings are visited most days to collect manioc and other crops such as bananas, pineapples, Amazon tree-grapes, cocona and other types of fruit; sweet potatoes, yams and other root vegetables; chilli peppers etc. The chilli peppers are used to flavour cooked fish and meat.

(Text provided by the Tuyuka communities of Pari Acima, on the Upper River Tiquié)

Unusual meals

Some types of food eaten by indigenous peoples might seem strange to people who live in cities. But, as well as being tasty, these unusual meals are nutritious and easy to find. Examples would be caterpillars, and queen ants. The queen ants come out in swarms, carrying eggs, when they are ready to start new colonies. People catch them as soon as they leave their nests. Then they eat them raw, or roasted and crushed (which turns them into a kind of tasty flour). (Text provided by the Tuyuka communities of Pari Acima, on the Upper Rio Tiquié)

What is paparuto?

Paparuto is a meal eaten by the Krahô Indians. They live in an area of Brazilian savannah (or cerrado) in the state of Maranhão. Other indigenous peoples living nearby, such as the Gavião Pykopjê, also eat paparuto. It is a traditional part of some festivals.Paparuto is a meal eaten by the Krahô Indians. They live in an area of Brazilian savannah (or cerrado) in the state of Maranhão. Other indigenous peoples living nearby, such as the Gavião Pykopjê, also eat paparuto. It is a traditional part of some festivals.

How do you make paparuto?

You start by grating one of the types of manioc root. If using mandioca-brava, first remove the poison from the pulp using a tipiti. (A tipiti is a utensil, made from dried leaves, used to squeeze poison out of grated manioc.)

Mulher Gavião Pukobye prepara paparuto. Foto: Prêmio Culturas Indígenas. Then banana leaves are laid on the ground in a cross shape. Manioc pulp is placed in the centre of the leaves. Pieces of meat are put on top of the pulp. This is covered with more manioc. Then the leaves are folded over, making a sort of square packet. The packets are tied up and taken outside to be cooked.

Paparuto assando na fogueira. Foto: Prêmio Culturas Indígenas. Stones are put in a fire and when they are very hot, the packets of paparuto are laid on top of them. The packets are then covered with more hot stones. Another layer of banana and palm tree leaves are laid on top of these stones. Then the whole lot is covered with earth. It makes a kind of oven for cooking the paparuto. When it is ready, the food is uncovered and taken to the main gathering space of the village, where everyone shares it. Sometimes maize is used instead of manioc.

Sources of information

- Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (ATIX) e Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)

Aprendendo Português nas Escolas do Xingu - livro 2 (2005).

- Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (ATIX) e Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)

Saúde, Nutrição e Cultura no Xingu (2004).

- Associação Escola Indígena Utapinopona Tuyuka, FOIRN e Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)

Histórias Tuyuka de rir e de chorar (2004).

- Julio Cezar Melati

Ritos de uma Tribo Timbira (1978).

- Pesquisadores e professores bilíngues wajãpi, Conselho das Aldeias Wajãpi (Apina), Instituto de Pessquisa e Formação em Educação Indígena (Iepé), Nucleo de História Indígena e do Indigenismo (NHII/USP), Museu do Índio - Funai e Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional - IPHAN/Minc

Jane Reko Mokasia - Fortalecendo a Organização Social Wajãpi (2008).

- When a boy or a girl approaches adolescence, it is time for them to learn about things they will need to do when they grow up and have families of their own. In many indigenous societies, girls and boys, at this age, are taken away from the community for a time. They only remain in contact with their closest relatives, who teach them what they need to learn. This is known as reclusion. During this period of reclusion young people have to obey the rules of the particular indigenous group that they are a part of.

Portugues

Portugues

German

German

Spanish

Spanish

Norwegian Bokmål

Norwegian Bokmål

Games

Games Myths

Myths How they live

How they live Ilya e o fogo

Ilya e o fogo String figures: Ketinho Mitselü

String figures: Ketinho Mitselü Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene

Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene