Every society has its own set ideas about how the world began and how different beings and elements came to exists. These provide explanations for the origins of human beings, animals, plants, rivers, landscapes, stars, the sky, and other things including the Earth itself. The ideas are often put into words in the form of stories. We call these myths!

What are myths?

Myths are stories about the distant past which give meaning to the present day. They explain how the world, and other things, came to be what they are.

They are generally told by older people, and listened to by younger people. Through them, important knowledge is passed from mouth to mouth, from one generation to the next.

A people’s myths are connected to their social lives, their rituals, history and ways of living and thinking. Myths express different ways of seeing life, death, the world, beings, time, space...

They are part of a society’s tradition, but tradition is always changing!

How do myths change?

Every time a myth is told it is changed in some way by the person who tells it. The storyteller’s experiences and values influence the way the myth is told, and the story is altered.

This is why myths are always changing and there are often various versions of the same myth. The same story has come to be told in different ways!

The Greek myths

Many people associate myths with the stories of gods and heroes of Ancient Greece: Hercules, Achilles, Agamemnon, Zeus, Aphrodite, Apollo, Artemis, Hermes...

There is a good reason for this. Our word myth comes from the ancient Greek word for myth: mythos.

The Ancient Greeks told myths about the origins of the world, the adventures of their gods, goddesses, heroes, heroines and other creatures such as the Minotaur, centaurs and nymphs.

- Some of these stories were written down by great Greek poets, such as Homer and Hesiod. Their ancient writings are the sources of what we know, today, about Greek mythology.

What is mythology?

Mythology is the study of myths and what myths mean. ‘A mythology’ means all the myths told within any one society or religion, or on a particular theme.

Indigenous myths

Indigenous peoples, like other societies, pass on their knowledge and their experiences by telling myths. Because they are peoples who, until recently, did not write things down, their main way of passing on this knowledge was, and in fact still is, by word of mouth. It is important to point out that, as well as myths, there are other forms of oral expression such as songs, ceremonial dialogues and other types of speeches...

Why are myths difficult to understand?

We have seen that myths are a way of transmitting a people’s reflections on various themes. But when we do not know these people, or their values and their culture, lots of details in the stories are difficult to understand. To make sense of myths you need to find out about the lifestyles and ways of thinking of the people who created them. That is the only way to properly appreciate the wealth of meanings the stories contain.

Is the same true for indigenous myths?

Yes. If we know little or nothing about different indigenous peoples, it makes it difficult to understand their myths. In fact, sometimes the more you look at these stories, the more you realise you still need to find out!

Do all indigenous peoples tell the same myths?

No. On the contrary, just as there are very many differences between indigenous societies, there are very many differences between their myths!

One myth may exist in dozens of different versions. There are more than 230 different indigenous peoples in Brazil. Just imagine how many different myths they tell in all! Even within an individual village different versions of the same story may be told...

Myths are original creations. That is why there is a great variety of them!

In spite of all the differences, do indigenous myths have some things in common?

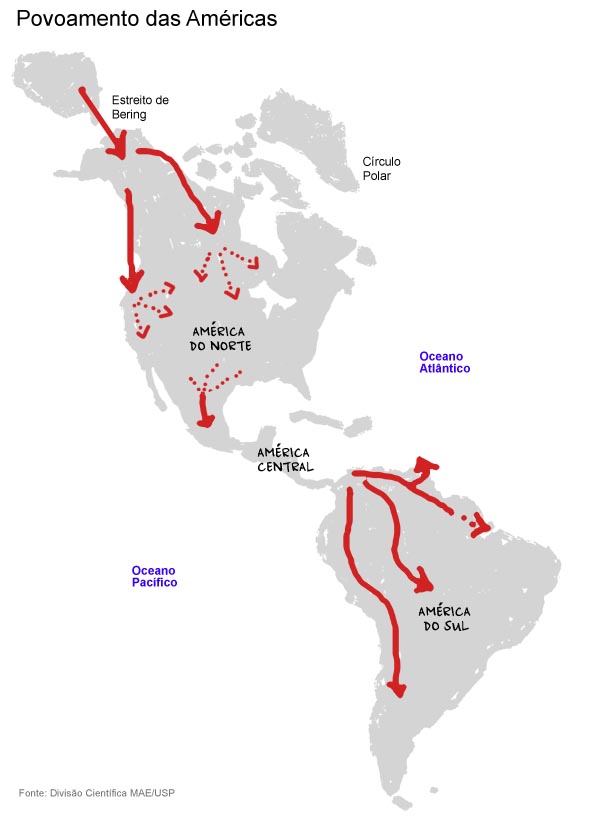

There are common themes in the myths told by Amerindians (all the indigenous peoples living in South and North America). That is because these peoples have lived side by side, exchanged goods and shared experiences for many thousands of years. It has led to a number of common characteristics.

Find out a about some common themes in the myths of Amerindians.

Stories about the sun and the moon

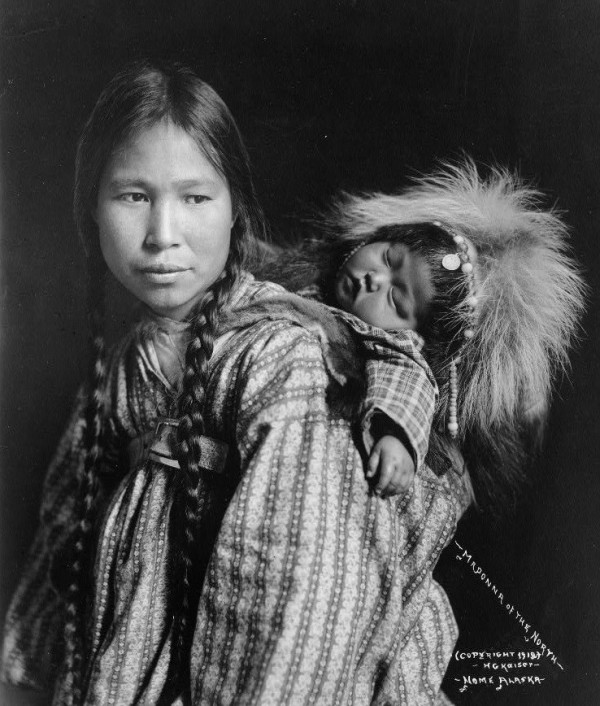

What story is told by the Inuit people?

Photo: Bob Bobster, 2009. Publicada sob uma licença Creative Commons (Atribuição 2.0 Genérica: Você deve dar crédito ao autor original, da forma especificada pelo autor ou licenciante). The Inuit, who live in the region close to the Bering Strait (to the north of North America) are also known as Eskimos. They say that, long ago, in a village on the coast, a man lived with his wife. They had two children, a girl and a boy. When their children grew up, the boy fell in love with the girl. Because he wouldn’t stop bothering her, she ran away to the sky. And she changed into the moon. But, since then, the boy has followed her in the form of the sun. Occasionally he manages to catch up and embrace her. This is when lunar eclipses happen.

What story is told by the Kanamari?

The Kanamari speak a language from the Katukina linguistic branch. They live in various areas of indigenous land in the Brazilian state of Amazonas. They say that many years ago, two children were born in a village. One was a boy and one was a girl. There were brought up together. One night, when they were older, the brother got into his sister’s hammock because he was in love with her. He only went after dark and never spoke, so his sister did not know who was visiting her.

Photo: Luiz Costa, 2004 But the girl wanted to find out. And she made a clever plan. She put paint made from jenipapo under her hammock. That night, the boy visited again. But, before he left, she marked his face with the paint. In the morning she found out that the boy with the mark on his face was her own brother. Both of them were embarrassed and they went off separate ways. The boy turned into the moon and the girl turned into the sun. From that day on, they never met again.

What story is told by the Taurepang?

Photo: Eliane Motta, 1984. The Taurepang live on the frontiers between Brazil, Venezuela and Guyana. They say that long ago Wei e Kapei, the sun and the moon, were great friends. They were never apart. At that time Kapei (the moon) had a clean, attractive face. But he fell in love with a daughter of Wei (the sun) and started to visit her every night. The sun didn’t like this. He told his daughter to throw menstrual blood in the face of her lover. From then on, the sun and the moon have been enemies. The moon’s face is stained, and he avoids the sun.

Stories of how fire was stolen

What story is told by the Ticuna?

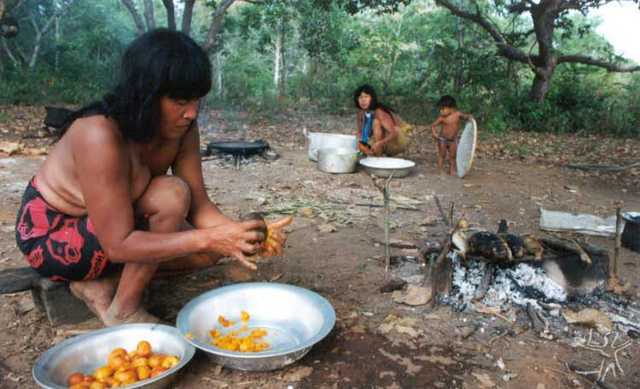

Photo: Jussara Gruber, 1979. In Brazil, the Ticuna live in the state of Amazonas. They also live in Peru and Colombia. They say that, long ago, men did not know about sweet manioc, and they did not know about fire. An old woman learnt the secret of manioc from some ants. And her friend, the nocturnal bird called the curiango, gave her fire. This bird kept the fire inside its beak, and used it to cook manioc. Other people could only warm their manioc in the sun, or under their arms.

Human beings thought that the manioc bread (beiju) that the old woman made was delicious. They wanted to know the recipe. She told them she cooked it using the warmth of the sun. The curiango thought this lie was very funny. It couldn’t stop itself from laughing! And that was when everyone saw the flames inside its beak.

Humans forced open the bird’s beak and managed to steal fire. Because of this, until today, curiangos have large beaks. And, from that day on, humans were able to cook their food with fire!

Adapted from: LÉVI-STRAUSS, Claude. Mitológicas. vol. 2. 2ª parte. p. 154.

What story is told by the Tembé?

Photo: Vincent Carelli, 1980 Long ago, the king vulture owned fire. Humans had to dry meat in the sun. They couldn’t cook it. But, one day, they decided to steal fire. They killed a tapir. When the carcass was full of worms, the king vulture came down from the sky with his friends. They all took off their feathers, and turned into human beings. They lit a big fire. They wrapped the worms in leaves and put them into the fire to bake. The men who were hiding near to the dead animal tried to steal fire, but they failed. Then they tried again and managed to steal fire from the vultures!

What story is told by the Katukina?

The Katukina speak a language from the Pano linguistic branch and live in the Upper Juruá region in the Brazilian state of Acre. They have a number of stories about the origins of fire. This is one:

Photo: Edilene Coffaci de Lima, 1998. One day when the jaguar went hunting, he asked the parakeet and the owl to keep an eye on his fire. He didn’t want the fire to go out. He said that if they looked after his fire, he would give them some of the meat he came back with. The deal was done! The parakeet and the owl stayed and looked after the fire. But when the jaguar got back, she ate everything himself. The next day, the jaguar asked the parakeet and the owl to do the same thing. Off he went again and at the end of the afternoon he came back from hunting. This time the parakeet didn’t hold back. He asked if the jaguar would give him a piece of meat to roast. The jaguar said she would. But she didn’t. She ate all of the meat herself.

The same thing happened for several days. Then the owl and the parakeet decided to steal fire from the jaguar. The owl had an idea. He said they should hide the fire in a hole in a tree. The parakeet did it before the jaguar came back. When the jaguar saw that her fire had gone, she was desperate. She tried to make fire again, but she couldn’t. She realised that she was going to have to eat meat raw. The parakeet carefully looked after the fire. It was hidden in a very tall tree. It burnt his big beak. That is way, today, parakeets have very small beaks.

It was the parakeet who first gave fire to human beings. Until he did, they hadn’t eaten cooked meat!

Adapted from: Comissão Pró-Índio do Acre. Noke shoviti – Mitos Katukina. Rio Branco: CPI-Acre, 1998.

There are many similarities between the myths of the Amerindians. But, if you look closely enough, you will see many differences.

Take a look at the animated film Ilya and the Fire. Ilya is a young warrior. He is the son of Cy, the Earth, who dares his mother to steal fire. The maker of this beautiful film was inspired by an indigenous myth about stealing fire!

Watch the film (in Portuguese)

Now here are two myths about the origins of cultivated plants. The first version is very well-known among the Iranxe Manoki and Menky Manoki Indians. The second is told by the Enawenê-Nawê.

The two stories deal with the same theme, but there are many differences between them.

Find out what these differences are!

What is the story told by the Iranxe Manoki and the Menky Manoki?

The Iranxe Manoki and Menky Manoki live in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso. They say that, long ago, a boy was very sad because he felt that his father didn’t like him. One day his mother told him to go gathering with her in the forest. On the way back, the boy decided he wasn’t going to return to the village. He asked his mother to bury him, there in the forest. He said she could leave his head above the ground so that he wouldn’t die. His mother was sad, but she did what the boy asked. Then she left without looking back, as the boy had told her to.

Photo: Ana Cecilia Venci Bueno When she got home, she told everything to her husband. Some time later they went to the place where the boy was buried. As they drew nearer they heard a beautiful song coming from a large garden full of things to eat!

The boy’s head had become a gourd. His legs and arms had turned into manioc. His teeth were maize. And his fingernails were peanuts. This was how plants grown by the Iranxe Manoki and the Menky Manoki first came into being!

What is the story told by the Enawenê-Nawê?

The Enawenê-Nawê are also from the state of Mato Grosso. They tell a similar story. But instead of a boy, it was a girl who first made the plants that they cultivate. This is the story:

Photo: Kristian Bengtson, 2003. One day a young girl asked her mother to bury her. Although she was sad, the mother did what her daughter asked, and buried her up to her waist in soft, cool earth. Once she was buried, the girl asked her mother to leave, without looking back. She also asked her to return once the first rains had fallen. Finally, she said she should bring her some fish and make sure to keep the earth around her carefully tended.

The mother did everything that her daughter asked and, when she returned she found a garden of beautiful, mature manioc plants. Every part of the girl’s body had become a different plant. This was how the various types of manioc grown by the Enawenê-Nawê first came into being. The mother often went back to her garden. She would weed the earth around the plants, carefully pull up the manioc roots and take them to her village where they provided food for everyone.

Other mothers saw what had happened, and they too buried their daughters. That was how plants such as sweet potatoes, yams and callaloo came into being.

Who tells these myths?

In every indigenous group there are people who are good at telling myths. They are usually older people who have a good knowledge of the cultural traditions of their people. It is common that these storytellers are shamans, or masters at singing traditional songs. Everyone in the community appreciates their stories.

When are myths told?

Índios Guarani-Kaiowá no caminho da roça. Foto: Marcello Casal Jr/ABr. Myths are usually told in the afternoons or early evenings when villages are at their quietest. This is when everyone has finished their work and is gathered together at home. Stories are also sometimes told during everyday activities such as walking through the forest, fishing or doing garden work.

Are some myths sung?

Yes. Sometimes mythical stories are sung in the form of songs.

The Marubo live in the Brazilian state of Amazonas. Their myths are sung by kechitxo. These are singers who go through a long apprenticeship. During an apprenticeship, an older kechitxo will teach the myth-songs he knows to a younger a younger relative.

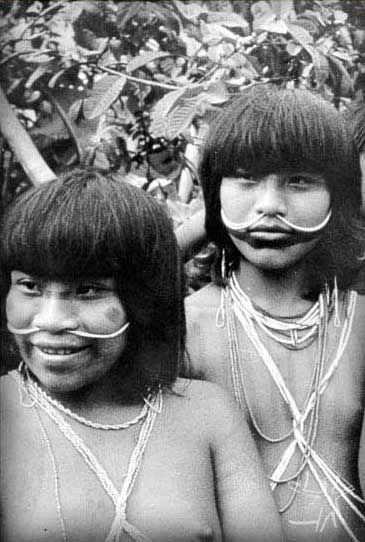

Photo: Delvair Montagner, 1975 The Marubo sing their myths to cure illnesses. For every illness there is a different song. Some songs are short. They last only 20 minutes. Others are very long. They may go on for 3 days. The longer songs often explain how people, animals, spirits and in fact the whole universe came into being.

The myths may be sung by a small number of people after eating at night, or during festivals attended by relatives from various different communities. On these occasions, young singers accompany the kechitxo.

Do indigenous children understand their people’s myths?

On the whole, these stories are very complex. They are difficult for children, who are still learning about the world, to understand. The old storytellers simplify myths when they tell them to young listeners. They take out complicated details. This way, children can start to get to know key parts of their people’s myths. Then, little by little, they go on to build up a greater knowledge of the wealth of their culture.

What are indigenous myths about?

These myths are about many things. They describe the adventures of heroes and beings which lived at ‘the beginning of time’ before the world and its different beings had been created. This was a time when, for example, humans and animals could talk to each other.

Myths also describe how humans, animals, plants and other being became different from each other. They recall conquests, discoveries, floods, catastrophes, transformations...

They describe how beings that lived at the beginning of time were changed, or came to create the world as we know it today. These beings taught humans how to live with each other, how to carry out festivals and rituals, to grow crops in gardens, to hunt, fish, make hammocks and many other important skills.

Read some myths about the origin of human beings

The Desana people live in the state of Amazonas, in Brazil, and in Colombia as well.

What story do the Desana tell to explain the origins of human beings?

According to the Desana, all humans had the same origin. They say that, in the beginning, when the world did not yet exist, a woman called Yebá Buró, or the Grandmother of the World, created five Thunder Men. It was these Thunder Men who were meant to make the first human beings, but they did not manage. So Yebá Buró made Great Grandson of the World, Yebá Gõãmu and, afterwards, his brother, Umukomahsu Boreka.

These two brothers and the third Thunder Man set off to create human beings. They took all the precious things they had. The third Thunder Man turned himself into a great snake which went to the bottom of the Lake of Milk. This snake was known as the Canoe of Transformation. It obeyed the two brothers’ commands and travelled underwater, like a submarine.

Between them, they created houses under the water and wherever they stopped they held rituals with the precious things they had brought with them. These precious things turned themselves into people. After this, the brothers created the languages spoken by the different peoples who live, until today, in the Upper River Negro region.

On the way back, the Canoe of Transformation carried the humans to a waterfall. This was where they first stepped on to dry land. But Yebá Gõãmu, the Great Grandson of the World, did not get out of the canoe. Instead, he created the Chief of the Tukano, who was the first to go down in the snake-canoe. He was followed by Boreka, the chief of the Desana. He also went down. The third was the chief of the Pyra-Tapuyo. The fourth was the chief of the Siriano. The fifth was the chief of the Baniwa. The sixth to make the journey was the chief of the Maku. The Great Grandson of the World gave each of them objects and powers to remain calm, to hold large festivals and get on well with lots of people.

The seventh to make the journey was the white man. He had a rifle in his hand. Yebá Gõãmu didn’t give him anything. But he said the white man would be a fearless person who would start wars to steal the wealth of others. The white man fired his rifle. Then he set off towards the sun...to start a war.

Sources of information

- Aracy Lopes da Silva

Mitos e cosmologias indígenas no Brasil: breve introdução, no livro Índios no Brasil (1992).

Mito, razão, história e sociedade, no livro A Temática Indígena na Escola (1995).

- Claude Lévi-Strauss

Mitológicas. Volumes O cru e o cozido, Do mel às cinzas e A origem dos modos à mesa. São Paulo, Cosac Naify (2004, 2005 e 2006).

- Jean-Pierre Vernant

O universo, os deuses, os homens (2000).

- Povo Kanamari e COMIN

Tâkuna Nawa Buh Amteiyam Amkira – Mitos kanamari (2007).

- Povo Katukina e Comissão Pró-Índio do Acre

Noke shoviti – Mitos Katukina.

- Tõrãmu Kehíri e Umusi Pãrõkumu

Antes o mundo não existia - Mitologia dos antigos Desana-Kehíripõrã (1995).

- Ana Cecilia Venci Bueno

Os Irantxe e Myky do Mato Grosso: um estudo do parentesco (2000).

- Dominique Gallois

Pesquisa etnológica entre os Tupi do Cuminapanema (1992).

- Gilton Mendes dos Santos

Da cultura à natureza: um estudo do cosmos e da ecologia dos Enawene-Nawe (2006).

- Pedro de Niemeyer Cesarino

De 'cantos-sujeito' a 'patrimônio imaterial': considerações sobre a tradição oral Marubo (2006).

Portugues

Portugues

German

German

Spanish

Spanish

Norwegian Bokmål

Norwegian Bokmål

Games

Games Food

Food How they live

How they live Ilya e o fogo

Ilya e o fogo String figures: Ketinho Mitselü

String figures: Ketinho Mitselü Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene

Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene