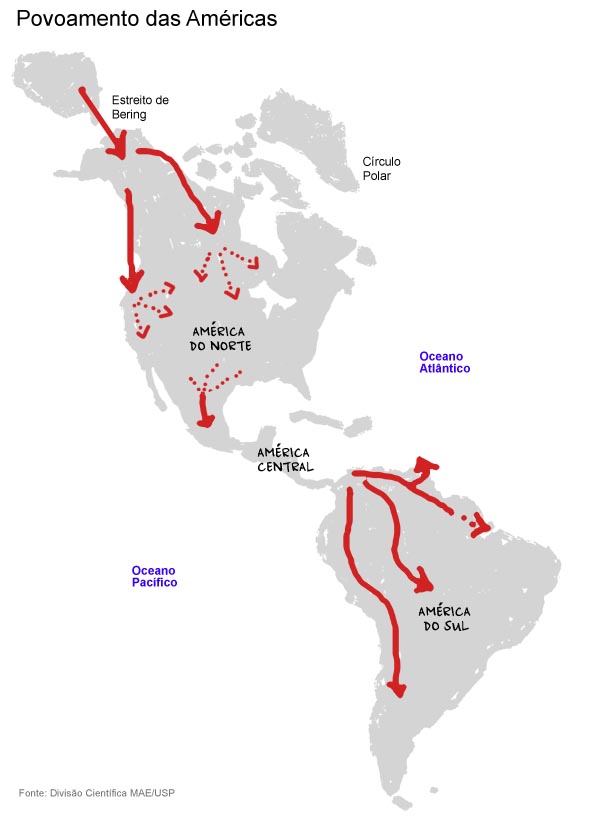

Everyone loves playing games. Children can spend whole days playing and making up their own fun. And adults like enjoying themselves too. When they can, they also get together to play sports and games. There are many different styles of play, but the point is always the same - to make the most of a particular moment in the company of friends. Games also help to develop skills that can be important for the rest of our lives. Playing is, in fact, a way of learning!

Indigenous people entertain themselves with all sorts of games and toys. Some are very well known among various indigenous peoples. Some are also common in non-Indian populations. (For example the peteca - a kind of shuttlecock played with by children across Brazil - or toy stilts.) Others are unusual and not so widely known. There are games only played by children. And there are games adults join in with and teach the children winning techniques they once learned! There are boys’ games and girls’ games. There are also games played with some sort of equipment. When this is the case, you can’t start playing until you have gone into the forest to find the materials you need and then learnt how to make the equipment for yourself. But that is all right, because making the equipment is part of the fun!Find out about the toys and games of different indigenous peoples!

Toys and games of the Kalapalo

- The Kalapalo live to the south of the Xingu Indigenous Park, in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso. They have many games and ways of playing. They play games on their own. They play games in groups. Some of their games are serious contests. Others are make-believe. Some are played in the main gathering space of the village. Others are played in water, or off in the forest. There are games which adults join in with, games only for children, and games played by adults and children together. Most mornings children go off to play very early in the morning. They play games until about 8am. Then they head home to help out with the daily chores. Girls help their mothers and older sisters make manioc porridge. They also join in with looking after their younger brothers or sisters. Boys help to make things, and they go with their fathers on fishing trips.At the end of the afternoon, the boys usually play football. They make their own goal posts and balls and their games are usually held in the centre of the village. But when it is time for the Kwarup (a ritual held by various indigenous peoples in the Xingu Indigenous Park) they have to find somewhere else to play. During the Kwarup the centre of the village is used for a fight called Ikindene.Find out about Ikindene and other games played by the Kalapalo!

Ikindene

Haroldo Palo Junior, 2006. Ikindene is a traditional game or martial art practised by the Kalapalo. It happens during the Kwarup ceremony, which brings people together from a number of different villages. Only men take part. (There is another ritual called Jamugikumalu, in which only women take part.) Ikindene competitors fight in the central meeting place of the village, two at a time. Their bodies are decorated with body painting, belts, ankle bracelets, shell necklaces and bundles of wool tied to the arms and knees.The game is taken very seriously. Old fighting champions fear being defeated by beginners, and beginners are wary of being injured. The Ikindene requires strength, courage, endurance and concentration.All year round people train for the fights that will take place during the ritual. When playing Ikindene, each man tries to knock his opponent on to the ground. He may also end a fight simply by touching the leg of his opponent with his hand. So the winner is the one who either touches his opponent’s leg, or who manages to knock his opponent right over.Watch a video of Ikindene fighting!

Ta

Before you can play Ta you have to make the equipment that goes with it. First this means making a sort of wheel from dried leaves. You then cover this with embira cork (from the bark of a tree commonly found in areas of cerrado). The cork has to be green (it is known as ta – the same name as the game.).

Haroldo Palo Junior, 2006. The aim of the game is then to hit the ta with a bow and arrow. You split into two teams. Each team stands in line, spaced well apart. One player is the bowler. They throw the ta in the air, towards the opposing team. The ta goes spinning past the opponents. And, as soon as it touches the ground they try, one after the other, to hit it with their arrows.

Haroldo Palo Junior, 2006. If no one hits the target, the two teams swap round. But if someone manages to hit the ta, then their team have another turn to fire and the bowler has to temporarily leave the game, to be replaced by another player.Ta develops bow and arrow skills, and also powers of concentration.What this video!

Heiné Kuputisü

This is a game of that requires a lot of endurance, and a good sense of balance. Each competitor has to hop on one foot (and must not change feet). A starting line is scratched into the earth and a finish line is marked about a hundred metres away.

Haroldo Palo Junior, 2006. If the competitor manages to hop all the way to the finish line then they are considered a winner. If they do not make it, that means they are not good enough yet, and they need to train some more. Even though speed is not important in this game, everyone tries to cover the distance as quickly as possible. But the overall winner is the one who manages to go the furthest. Boys and men play this game in the open space at the centre of the village.Watch this video to see people practising Heiné Kuputisü. When they are practising, they race two at a time and each of the competitors represents a different team.To watch click here.

Toloi Kunhügü

Haroldo Palo Junior, 2006. This game happens at the edge of a lake or a river. Whoever comes up with the idea of playing it has to pretend to be a hawk. They are then in charge of the game. “The hawk” draws a big tree in the sand. It has many branches. The other children pretend to be “little birds”. Each little bird chooses a branch and “makes a nest” on it, then sits there.The hawk has to hunt the little birds, so they leave their nests and gather together at a spot not far from the tree. They stamp their feet and tease the hawk by singing a song.

The hawk comes slowly towards them. Then, when it is very close, it gives a jump and tries to catch the birds. They, in turn, run in all directions, dodging this way and that to confuse the hawk. When they need a rest they can go back to the safety of their “nests”. When the hawk manages to catch one of them, that child is out of the game. They have to stay put on a particular spot, near to the foot of the tree. The last little bird left playing becomes the hawk in the next game.Toloi Kunhügü is a game that develops many skills including concentration, reactions, agility and awareness of time.Watch this game!

Yudja games

The Yudja speak a language of the Tupi linguistic family. Some of the Yudja people live in a group of 6 villages situated near to the river Xingu, in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso. Others live at the far end of the river near to a town called Altamira, in the Brazilian state of Pará.

The text that follows was written by children from a village called Tuba Tuba, together with people working on the Xingu/ISA Programme.

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. We are Yudja children from the Tuba Tuba village in the Xingu Indigenous Park in Mato Grosso.Us boys from the village like playing with our bows and arrows. We first start learning how to make small bows from our grandfathers, fathers, older brothers and friends.

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. We make bows and arrows from all sorts of material just to play with and to learn how to fire them. The most difficult thing is to fix the feather at the end of the arrow to make it fly straight. We go with our fathers on fishing trips. We also go fishing on our own, down by the river. But when the older men go hunting we cannot go, because it’s difficult to keep up with them.We have a bow and arrow championship to see who the best at firing is.

We like making little planes. We use leaves from trees and other things to make rotors like you get on a helicopter.

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. Us girls like making bead bracelets and necklaces.

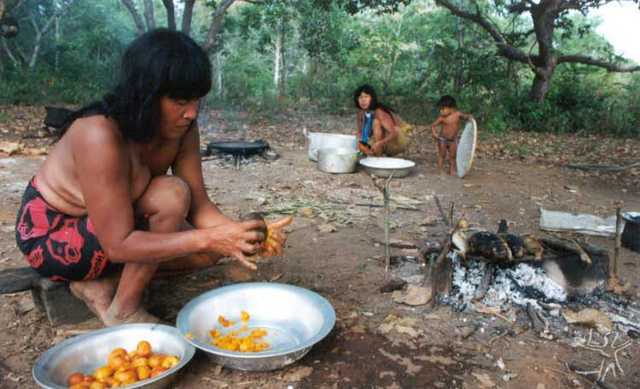

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. At home, we help our mums look after our younger brothers and sisters, and cook fish, and make porridge. By helping we then learn to do these things on our own.We also help in the gardens and carry back manioc, potatoes and other things.

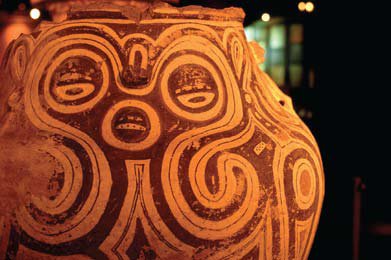

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. We get water from the river to cook and wash with. We wash clothes and dishes when we are still very small.We are learning how to do body painting and to make dishes and cooking pots out of clay.

We like playing “catch” in the river, sliding down the river bank, and drawing animals or people in the earth...

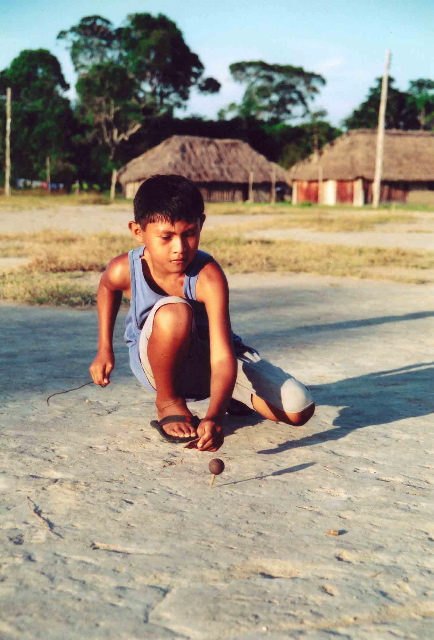

We also make spinning tops out of the seeds of tucumã palm trees....

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. We play with string.

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. We also have songs for hand-clapping games and playing in circles. At night we like playing in the village gathering space and singing the songs that go our games, or the songs that people sing at our festivals.

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2009. We go to the school in our village. We study in our language and in Portuguese as well. We hear stories. The elders in the village come and tell us stories during our lessons.

Galibi Spinning Tops from Oiapoque

The Galibi people live in Oiapoque, to the far north of Brazil. They migrated from French Guyana in the 1950’s. They are originally from the River Mana region, but they came to live on the right-hand bank of the River Oiapoque, in the north of the Brazilian state of Amapá. Most of the Galibi still live back in French Guyana. There they are known there as the Kaliña people.

Renata Meirelles. Two Galibi boys, called Valdo and Donato, are trying to make spinning tops out of the seeds of a tucumã palm tree. These are special tops because they “sing” as they spin. Valdo and Donato are trying to make them the way their father taught them to. First they find the best seeds. Then they make small holes in them. Then they clean and scrape out the insides of the seeds – so that they are completely hollow.But, unfortunately, the tops they make will not spin. Nor do they make any sound. Having failed, they put the spinning tops in their pockets and wait for their father to get back from the forest at after dark. When he arrives, their father, who is called Miguel, takes a look at his sons’ spinning tops. He tells the boys he will teach them how to make them properly, but they will have to wait until later the following day.Valdo and Donato live in a place called São José. It is a village made up of eight wooden houses, surrounded by mango, cashew and guava trees, gourd plants and other trees known in Brazil as jenipapo, tucumã and inajá. A handful of children live there. They like playing games that they have picked up from children in the city of Oiapoque. For example, they play with petecas (shuttlecocks that you hit with the flat of your hand) and with paper kites. But they have also been taught to make traditional toys by older people in their own community. Among these are the singing spinning tops made from the seeds of tucumã trees. As he had promised, Miguel shows his sons what they need to do. He does not explain anything. He just makes a tucumã-seed spinning top in front of them. They watch him and make their own tops, together with their father. They do not speak, or ask questions, or request help.And this time they work! All the spinning tops spin and sing at the same time.

Renata Meirelles. The noise attracts Seu Geraldo, the oldest man in the village. He cannot hold back his delight when he sees his grandsons playing with the toy he used to like most as a child.With the boys around him, he describes how they used these spinning tops to hold competitions when he was young. Lots of children would get together, each bringing their own fane (the name for a tucumã-seed spinning top in the Kaliña language). Then they would get a hammock. Four children would hold the corners of the hammock so that the cloth was stretched tight. The others would spin their tops together on the cloth. That was how a fane competition would start. The aim was to see whose top would spin for the longest, without toppling over, or falling off the hammock. When the village elders tell stories like this, the children learn both how to make and how to use the toy. And this is how knowledge is passed from one generation to the next.

Xavante stilts

In general children like to show off how big and strong they are. You often see them making gestures to exaggerate their size and strength.Maybe this is why so many children around world end up walking about on stilts.

Renata Meirelles. When the children want to play on stilts in one of the Xavante villages, in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, first of all they go into the forest. They take machetes with them and they have to find their toy. It is there waiting for them, but hidden in a particular tree in the forest. It can take hours before they find a tree trunk that is long enough and straight enough and which has a Y-shaped fork at one end that is not too twisted or too open (This is what you need to stand your foot on,). Their search would be made a lot easier if the village was not situated in the middle of the Brazilian cerrado, a region covered by short trees with twisty trunks. Once they manage to find the right tree trunk, they face their second challenge. They have to find a second one to match it. This way the “hunting expedition” for stilts hidden in the forest can go on for a whole morning. The fork footrests on the stilts mean that the children’s feet cannot rest parallel to the ground. Their feet have to twist inwards. This is a little bit uncomfortable when you walk. But Xavante children like showing everyone their strength and toughness. They challenge each other to see who can walk the furthest without falling over. The whole day passes without the children starting up a new game. For them, one game per day is enough.

Pull Out the Manioc

This game remains a firm favourite in many indigenous communities, even though it is little known to non-Indians. And it is popular because, to play, you have got to be strong!In the Brazilian states of Espírito Santo and São Paulo, Guarani children call the game “Arranca Mandioca” (“Pull Out the Manioc”, in English). This is because the way you play is a bit like the way you collect manioc roots - an activity well known to indigenous children.When they decide to play this game, they gather near a tree and get into a line, squashed up close, with their hands on the shoulders of the child in front. They then walk, in this line, up to the tree and sit on the ground. Whoever is at the front of the line grips the tree. They others cling to each other’s arms and legs. Then one child (who has to be very strong) has the job of “pulling out” the manioc roots – which are the children themselves.The first in line (the one who is gripping the tree) is the “owner of the manioc plantation”. They give permission for the “manioc roots” to be removed one by one. Then the children are each pulled out of the line, using whatever force is needed to get them free.Among the Guarani, all sorts of different strategies are allowed in order to pull the children out. You can tickle, pull by the legs or ask for help from one of the children already pulled out of the line.

Renata Meirelles Among Xavante children, however, it would be unthinkable to do things like tickling. In the Brazilian cerrado, where these children live, the girls and boys know call this game “Tatu” (the Portuguese word for an “armadillo”). This is because it is very difficult to catch an armadillo once it has gone down its hole. However you try, no one can pull an armadillo out with their bare hands. You can pull by the tail, but it will dig its claws into the earth and nothing will shake it free!The Xavante attach a lot of importance to strength, toughness and courage. Even when Xavante children are playing, these qualities are important. In the game Tatu, for example, children will only let go of the others if the person “pulling out the armadillo” does it just using their own strength.This game is a guaranteed success in all sorts of situations and there is laughter from beginning to the end.

Peteca

A peteca is a kind of shuttlecock hit with the flat of the hand. The word peteca has a Tupi origin. It means “to smack or hit with your hand”. And these days it is the most common name for this toy, played with by children all over Brazil.Just as they did in the past, children have to wait until harvest time to make this toy. Then they use dry maize leaves to weave different bindings and knots and make petecas in different shapes and sizes.Find out a bit about petecas made by different indigenous peoples.

Renata Meirelles, 2007. Senhor Toptiro is the chief of a Xavante village called Abelhinha, in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso. He says that one game every day is plenty to keep children happy. For people living in big cities, where time and everything else moves quickly, it might seem unbelievable that a group of four to thirteen year-olds could keep themselves busy for a whole day playing just one game.But going off to find dry leaves in one of the village gardens takes the children on a journey full of adventures.Then they need to be observant and skilful to turn their dry leaves into good petecas. They need time to look, experiment, make mistakes, make corrections and learn.Senhor Toptiro gives a mischievous smile as he finds himself surrounded by boys and girls copying the movements of his strong, old hands as he twists dry leaves into a tobdaé (the traditional peteca of the Xavante). As well as using his eyes and his fingers, Senhor Toptiro uses one of his toes. He ties string made out of dried buriti leaves to it. Then he pulls it into the tight spiral which holds together the base of the toy. This design is different to some of the other peteca designs described below.Once ready, Xavante petecas are light, agile toys. And they are used in a game which demands the same qualities from the players: lightness and agility.

Renata Meirelles. The game is a version of "catch" or "it". It is played with six tobdaés. There are no limits to the area the children play in and two people take part in each game.Each player starts the game with three tobdaés. The aim is to throw them at your opponent while, at the same time, dodging the ones thrown at you. If you get hit by a tobdaé, you are out. A new player takes your place and the game starts again.Every time maize is harvested in village gardens these peteca contests start up, and much fun is had. It is a game played in different ways in indigenous villages from the cerrado, where the Xavante live, to the Atlantic Forest in the state of São Paulo, which is home to Guarani indigenous communities.The Guarani name for a peteca is a mangá. And theirs is the true ancestor of the petecas played with by children across the state of São Paulo.Their petecas are made using maize leaves both on the outside and the inside. The maize leaves are used fill the peteca, they hold together the round base, and they are also used to attach feathers in a strong loop.Nicolau is a much-loved Guarani teacher. He plays mangá with the children in his community. They have another type of peteca called a yó. This is not made from of dried maize leaves. You use a corn cob that has been split down the middle. Two identical chicken feathers are carefully fitted into the corn cob. They make the toy spin like the rotors of a helicopter. The challenge is to see who manages to throw their yó the furthest.These are some examples of the way different indigenous peoples make petecas. They show that the peteca is just as popular among the indigenous population as it is among non-Indians.

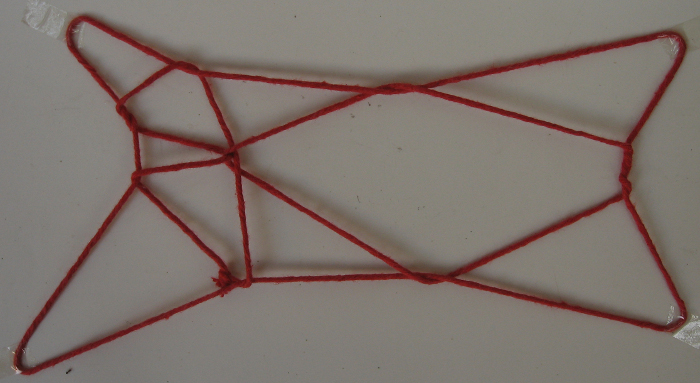

String figures and games

Renata Meirelles, 2007. Children and adults all around the world know how to make hand-designs out of string. They use their hands to make images from everyday live: a broom, a star, a hammock, a house, a chicken’s foot, a fish, a diamond, a balloon, a bat... They also know how to do amazing magic tricks such as cutting through their necks, knotting together two lengths of string with their mouths, passing someone’s hand through the string, undoing knots with a single pull, doing magic with their feet and more besides.About 600 Wapixana Indians from a little over 100 families live in a village called Canauanim, in the Brazilian state of Roraima. Among them is Dona Júlia, who is the mother of the tuxaua, or village chief.

Renata Meirelles, 2007. ADona Júlia knows many stories. She also teachers the young people in the village to spin cotton using a tool made from a tortoise shell. Once she has made a number of good, white, balls of cotton, she uses them to weave hammocks. And she likes using the pieces of string left over to make figures and do magic tricks. Her relatives and grandchildren look on as she ties a knot at the end of a piece of string and starts demonstrating tricks she can do with it.This way, from hand to hand and often from grandparent to grandchild, string figures and games pass between cultures, spread among different peoples, and develop into amazing new designs!One of Dona Juliá’s favourite games is a magic trick called Matar Carapanã. In English this means “Kill the Mosquito”. It is a trick also known to the Kalapalo people, who live in the Xingu Indigenous Park, in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso. They call it Ketinho Mitselü. The Kalapalo use a long piece of string made from dried leaves of a buriti palm tree. This is plaited together and the ends tied up. They quickly weave the string with their fingers, creating all sorts of different designs. They make animals. They make characters from indigenous myths. And they make playful images of things from everyday life.

Haroldo Palo Junior, 2006. Grown up men and women know how to make all sorts of complicated string figures. Children make simpler designs. But all of them make the string patterns incredibly quickly. The children make string figures and pass them onto a friend’s hands. The friend transforms the design and then changes it back. As well as being fun, string figures and games develop creativity, memory and attention to detail.Watch this video!

Sources of information

- Renata Meirelles

Giramundo e outros brinquedos e brincadeiras dos meninos do Brasil (2007).

- Marina Herrero

Jogos e brincadeiras do povo Kalapalo (2006).Na Internet

Portugues

Portugues

German

German

Spanish

Spanish

Norwegian Bokmål

Norwegian Bokmål

Myths

Myths Food

Food How they live

How they live Ilya e o fogo

Ilya e o fogo String figures: Ketinho Mitselü

String figures: Ketinho Mitselü Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene

Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene